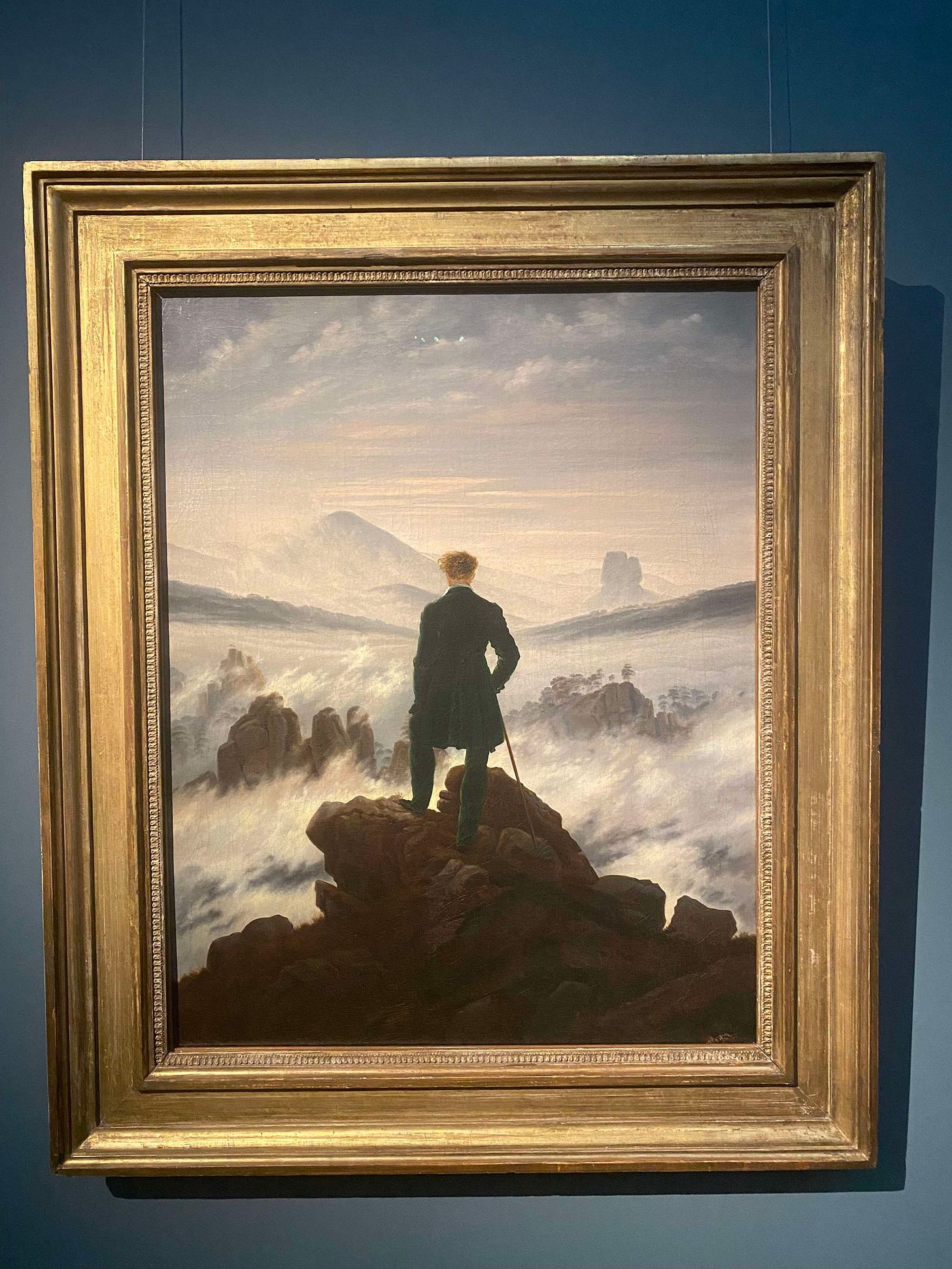

There have been few paintings or pieces of art that I have seen which have moved me. I like art and I can appreciate good art; but I can struggle to feel inspired by art. However, this has never been the case with one painting.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog is a piece that moved me the moment I first saw it. For close to a year now, it has been the wallpaper of my phone. Back in July, I travelled to Hamburg for the sole purpose of seeing the painting.

There is something about the figure in the centre of the painting, staring out into the fog that lays before him, that I have always felt drawn to. I want to know who he is and where he is. What is he looking for? How does he feel? Is he scared? He doesn’t appear to be. His back and shoulders are straight. He almost appears to welcome the unknown before him.

As I stared at the painting, I could not help but think of a quote I heard once: Feel the fear and do it anyway. I didn’t realise how much this painting would help me three days later, when I was in Mostar, in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

I arrived at my hostel late at night. I sat down in the communal area and began talking to the other guests who were there. I knew little about Mostar and I knew of nothing to do in the city, apart from the one thing that I had come to do.

In 2012, Australian comedy duo Hamish Blake and Andy Lee went on a televised road trip across Europe. As part of their travels, they ended up in Mostar where they jumped off the Old Bridge, a 22-metre high jump in the city’s centre, into the river below. In doing so, they became members of the Mostar Diving Club.

The 12-year-old version of myself was captivated. That jump and the goal of joining that club, was a desire that I kept in the back of my head. I had no experience jumping from cliffs, but it became a goal that I knew I had to grab a hold of if the opportunity ever arose.

When I told the others at the hostel about my plan, I was met with looks of concern. Some thought I was kidding. I knew the jump was dangerous. Since 2012, at least four people have died doing it, and one guest told me how a few days earlier, a young Australian male had been paralysed after he jumped. Seeing as I could also fit that description, this was not exactly what I wanted to hear.

I was undeterred though. 2 days later, I made my way to the bridge, found a member of the club and told him I was interested in jumping. He took me into the club house, made me sign a waiver (of which a word I could not read) and then took me to the platforms where the aspirational practised.

The way my instructor’s face twisted when I told him the highest I had ever jumped from was about 6 or 7 metres, did not fill me with hope.

“We’ll start you from 12 metres,” he told me.

After a few pointers, I made my way to the platform. For the uninitiated to diving - of which I include myself - 12 metres is a frightening height to leap from. Standing there, I had no idea how I was going to muster the courage to potentially leap from the additional 10 metres that made up the bridge.

My first jump from the 12-metre platform was not great. I straightened myself too soon meaning when I hit the water, I hit it hard. My instructor was not impressed. He shrugged his shoulders when I got out and said, “It’s not great.”

The next jumps were not great either. I continued to hit the water hard and I could feel each jump slap my back and thighs. From greater heights, this could be harmful. I had been told by the instructors at the start of training that if I was not good enough, I would not be allowed to jump. I began to think that the goal I had held onto for over a decade may be slipping away.

My instructor offered an alternative to correct my form. He told me to simply lean forward over the platform until I started falling, instead of jumping outwards. Following this advice, I felt that I started to make progress. Though it never became easier to lean over the platform and start falling, my jumps progressively got better. The instructor was impressed and I began to think I was in with a chance.

“I think you should have a go at the 17 metre jump,” he told me.

From below, the additional 5 metre distance from the 12-metre platform to the 17-metre platform did not seem much. From the 17-metre platform itself, it was monumental.

The crowds that formed on the beach did not seem to care for any one jumping from the 7m or 12m platform. However, once you were higher, there was more attention. I stepped up to the edge, leant forward, and fell. The jump was far from perfect but it was acceptable - I was unharmed. I got out, shaking, not from the cold but from adrenaline. We decided to take a break and on the walk back to the clubhouse, I was told that I could be ready by the afternoon.

I jumped from the 12-metre platform again and then twice more from the 17-metre platform. After that second jump, I had no interest in climbing to the top to continue practising. I wanted to jump from the bridge.

My instructor had stayed at the clubhouse while I practised. I went to see him and check if he thought I was ready.

“You hit the water strong, no splash,” he said to me. “For me, you can jump.”

Another of the instructors asked if I wanted to. I had not come that far and waited that long to say no. “Why not? Let’s do it,” I told him.

On the walk up the bridge, I attempted to appear calm and not look towards the water below. Inside, I could feel the beating from my heart reverberate throughout my whole body.

My attention was brought back to the present moment when I was told to wait no longer than 15 seconds before jumping.

“Don’t jump after one second. You won’t be ready,” my instructor said. “But don’t wait longer than 15 seconds. Otherwise, you will think too much.”

The first thing the club members do is signal any boats travelling up and down the river to stop. They then clear a space for you on the bridge, so you can hop over the railing. In the midst of all this, I was offered one last one last piece of advice: “Remember, you can handle it. So handle it.”

It was time. I hopped up on the stones. I climbed over the railing. Anybody daring enough to jump gains a significant crowd, but I was oblivious to all those recording on either side of me. From atop of the 17 metre platform, I remember looking at the bridge and thinking it was not much higher. Now, on the bridge itself, I saw just how much higher it really was.

Standing on the other side of the railing, the rushing water 22 metres below me, I repeated the seven words that had come to my mind when I stared at Friedrich’s painting in Hamburg: Feel the fear and do it anyway.

I stood up straight. I held my arms out beside me.

And I leant forward.

To me, in the process of plummeting 22 metres, the fall seemed quick. It was only after I watched it later that I realised how long I fell for. However, I had done it. My entry was good and I surfaced to applause from onlookers on the bank and the bridge. I looked back up, smiling and swearing to myself. 12 years after I had first been inspired, I had done it. I had become the 4224th member of the Mostar Diving Club.

After paying the €30 entry fee, my entry into the Diving Club was confirmed. I was told that if I wanted to jump again, I just had to say my number so they could look me up in the book and then I would be able to jump for free.

I collected my certificate, thanked the instructors, and then told them I had no interest in ever doing that again.

woah, its so cool that u travelled to actually go see the painting!

Something I could use for everyday life, but I won’t be jumping off any bridges thanks. Nice piece.